Jenna Gribbon Substitutes Power with Power

The Frick’s “Living Histories” series provokes strong reactions as the contemporary Queer painter takes on Holbein

What Am I Doing Here? asks the title of Jenna Gribbon’s painting currently installed at the Frick Madison. Gribbon isn’t the only one wondering. The Frick’s normally quiet Instagram account seldom garners a dozen comments per post. But the two posts featuring Gribbon’s painting have more than 166 comments combined. And those comments are divided into two very adamant camps.

Gribbon’s oil painting is installed at the Frick’s temporary home in the Brutalist Breuer building as part of “Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters,” which places contemporary art among the Frick’s classics. The yearlong project features the works of New York-based artists Doron Langberg, Salman Toor, Jenna Gribbon, and Toyin Ojih Odutola juxtaposed with artworks from the permanent collection. The aim is to add perspectives that have been traditionally excluded from the Frick into the conversation.

The museum’s curatorial staff is taking advantage of the collection’s provisional, modern space to mount exhibitions that usually fall outside of the Frick’s (and its audience’s) comfort zone.

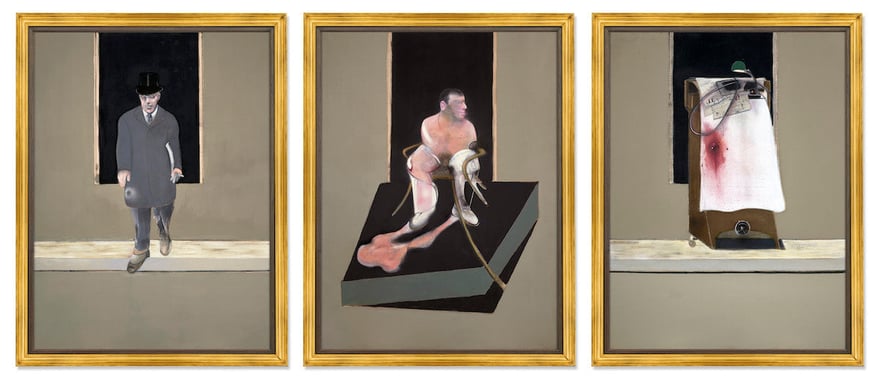

Jenna Gribbon, What am I doing here? I should ask you the same, 2022

Jenna Gribbon, What am I doing here? I should ask you the same, 2022“Not exactly a masterpiece…,” wrote one Frick Instagram follower. “Horrible and bad taste,” wrote another particularly combative commenter. “Belongs somewhere, but NOT at the Frick. Especially regarding Holbein, one of the very greatest portaitists,” said a third. “Alright already with this”art” barf….,” complained another–though that comment might have easily been directed towards the overheated opinions on both sides.

The defenders of the Frick’s presumably exalted status only seemed to provoke an outpouring of support for Gribbon’s work, her identity, and her talent. “Beautiful painting, amazing artist, a ton of depth to both the lens of her work and her technique,” wrote one defender. “If the trolls turned amateur art critics could wrap their minds around anything other than their narrow view of the world… hell they might even learn something from a timely and thoughtful exhibit like this!”

In a visit to Gribbon’s What Am I Doing Here? I Should Ask You the Same, 2022, the painting felt right at home amongst the Frick’s famed collection. The rich textures and jewel tones make it a worthy stand-in for Hans Holbein’s equally lush Thomas More, which is out on loan at the Morgan Library.

Hans Holbein, Portrait of Sir Thomas More, 1527

Hans Holbein, Portrait of Sir Thomas More, 1527Where Holbein’s Thomas More is power personified, Gribbon’s sitter takes power into her own hands. Seated in a confrontational pose with her legs splayed, hands bared, and gaze trained steadily on the viewer, the painting depicts Gribbon’s partner, but the painting is hardly a domestic scene.

Gribbon’s painting borrows a slew of visual elements from the Holbein portrait it replaces. The green chair Gribbon’s partner, Torres, sits upon draws directly from the green velvet curtain in the background of Thomas More. Torres wears a purple velvet suit that references More’s iconic sleeve. Her single exposed breast echoes More’s Tudor rose pendant.

Like Holbein, Gribbon masterfully activates texture to evoke opulence. Her sitter’s supple velvet suit ripples and shines in the harsh spotlight. Its depth of color and sense of tactility emanate from the canvas. Framed by the suit, the sitter’s soft skin is invitingly imperfect, with the folds of her midsection and veins in her hands lending her an unidealized intimacy. Her exposed skin gives her an aura of self-assuredness, as opposed to vulnerability. The sitter dons six rings of colorful, glittering stones off of which Gribbon reflects the same glistening light that resides in the figure’s gray-blue eyes. She is encompassed by a rich red coat that uses hue to create a focal point for the viewer. Gribbon’s subject sits in a New York City apartment in lieu of Holbein’s stately interior, the rattling pre-war radiator a tongue-in-cheek reference to the difference between the painters’ two worlds .

“When we encounter a portrait in a museum, our thoughts often turn immediately to who the subject is, and what made them special enough to be enshrined in that rarified space,” explained Gribbon in an interview with Frick curator Aimee Ng. “Holbein’s subjects are depicted with legible status symbols that signal power and social status—essentially their right to be featured in the painting.”

Like Holbein, Gribbon paints a powerful figure. Her sitter’s unapologetic pose–reminiscent of the notorious subway “manspread”–demonstrates no hesitation to take up space. Her aforementioned outfit evokes the historical colors of royalty while also ensuring the wearer would never go unnoticed. Unlike Holbein’s More, depicted in three-quarter view, Gribbon’s portrait engages the viewer head-on. Her piercing eye contact deters any question of her belonging.