Sotheby's Waves the White Flag

Can artists, galleries and auction houses live together in peace?

A year after joining Sotheby’s, the auction house has announced Noah Horowitz’s first initiative. The former executive at an art fair that stoked the perception of conflict between galleries and auction houses, is launching a program to give galleries and their artists direct access to auction. In the new Artist’s Choice program, artists and galleries will place works at auction while earmarking 15% of the sale proceeds (split evenly between Sotheby’s and the consignors at 7.5% each) for a charity of the artist's choice.

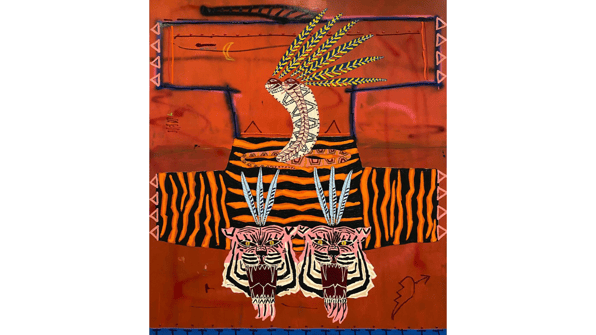

Along with the announcement, works by Alexandre Lenoir, Atsushi Kaga, Kennedy Yanko, Kevin Beasley, Todd Gray, Vaughn Spann and Katherina Olschbaur were unveiled for the initial launch during the September 30th Contemporary Curated sale, Sotheby’s mid-season sale opening the Fall Contemporary market.

The sale is a trial balloon recasting the relationship between artists and the auction house. But its not the first time Sotheby’s has tried to create this beachhead. Fourteen years ago, Sotheby’s held Damien Hirst’s nearly-$200-million-grossing “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” sale. In the immediate aftermath, Hirst’s sale was judged a raging success and other artists with similar public and market profiles were talked of as the next candidates even though the sale took place at the beginning of the global financial crisis on the day Lehman Brothers went bankrupt.

The worsening financial crisis and retreat of the art market squelched any interest from other artists to pursue such a grand strategy. Since then, no artist has had Hirst’s audacity to mount such a sale.

The long-term effect on his market might have something to do with it. Even after nearly a decade and a half, Hirst’s prices and market have not recovered to the pre-2008 sale level. You might ask, Who cares? A huge portion of that $200 million went directly to Hirst with no middleman to share in the proceeds. In an age of high auction prices where the artist does not directly benefit, one can easily see the beguiling attraction of direct consignment.

There’s also the fact that the collapse in Hirst’s market might not have only been the result of the sale. Of course, none of the artists included in Sotheby's Artist Choice program are remotely like Hirst in the size of their markets, scale of production or price of their works.

Nevertheless, Hirst's example hasn’t stopped artists or galleries from consigning their own work directly to auction. A number of important artists have been seen, or suspected, to be consigning directly from their studios. Others have collaborated with the auction houses to access the auctioneers’ robust marketing lists through private selling exhibitions. The ones that do access the auction house’s marketing platform tend to be artists who take direct control of their markets.

Galleries still have a more fraught relationship with the auctioneers. Perhaps that’s why Sotheby’s and Horowitz are approaching this new venture in a gingerly way, both in the choice of artists and in the charity structure.

Of the seven artists included in the first sale, only two—Atsushi Kaga and Vaughn Spann—have had much of a track record at auction. The reason the work of young artists comes to auction is a function of the gallery system. Galleries try to manage an artist’s career. They do this by being selective about who gets the work. As we all know, they give preference to known and influential collectors, buyers with museum connection and institutions. Why? All of this helps validate an artist and raise their profile.

Auctions are a way to circumvent waiting lists and Sotheby’s sees this program as a way to entice galleries and artists to access that demand—and reap the benefits—themselves. “With the right work, at the right time,” Horowitz told the Financial Times, “artists and galleries can directly capture the upside at auction.”

That’s a little weird. Instead of letting a formerly trusted collector undermine the artist’s market, the pitch seems to be that the gallery and artist should do it themselves. The complaint about auctions isn’t really the lost revenue. It’s that these sales feed on each other, unleashing a frenzy in an artist’s market. It’s a bit like a rancher saying she would rather start the stampede herself instead of letting a cattle rustler do it.

That said, no one is likely to charge over a cliff later this month during Sotheby’s sale. None of the seven artists, including Kaga and Spann, seem to have reached the market temperature we’ve seen for equally new artists whose prices have reached well into the seven-figure range. So the artists and galleries that have joined the program aren’t really looking to mop up market liquidity in a kind of lottery for just one work.

Presumably, these seven artists and gallerists know their markets. That’s the gallery’s job. They know roughly how many buyers there are and how much work the artist makes. The problem is that the buyers don’t necessarily know or believe the gallery when they say there’s demand at a certain price level.

Something similar happened more broadly in the art market nine years ago, in the wake of the financial crisis, money had begun to flood back into art in 2013 through the secondary market. Many buyers were distrustful of secondary dealer prices then creating something of a standoff between buyers and sellers. Neither would blink.

Bringing works to auction broke the tension. Throughout that year, the action in the art market was in public sales. Strong prices launched a three-year cycle of rising volume as buyers (often) proved happier to pay more at auction for the visible proof of a counter-bid. On a much smaller scale, Sotheby’s Artist’s Choice program is meant to do the same thing. It helps establish a public price above where the gallery sells primary work. This provides buyers with visible proof of demand but also allows the gallery to set prices below that level where they can still control where the work goes. Horowitz described it as “a useful way for some to set a [public] price for their work, which is helpful to new buyers.” A side benefit is the goodwill the gallery gets from the collector who believes they have gotten a discount.

Even with the gallery working behind the scenes to channel buyers through Sotheby’s (another strategic side benefit for the auction house) there’s no guarantee of success. That’s where the charity angle comes in. One key enticement for artists is the opportunity to use auctions to fund their passionately held causes. But the charitable donation is also a means to provide cover for everyone involved. A failed auction for charity is still a noble effort. A failed attempt at re-setting primary prices is potentially as fatal to an emerging artist’s career as prices rising out-of-control.

At the hammer prices one might hope for, judging from the estimates on these seven works, a 15% donation is going to amount to less than $50,000. Why not donate the entire proceeds? Two reasons, US tax law is unfair to artists who donate work for charity. The artist cannot get a deduction for the price paid. The artist is only allowed to deduct the cost of materials. That’s their donation. All of the rest of the value of the work—the value of the art itself—simply evaporates as a tax deduction. That removes much of the incentive for the artist to donate the entire value. Also, if the artist and gallery donated the entirety of their share, that would put Sotheby’s in something of an awkward position.

What are the long-term prospects for Horowitz’s program? It’s really not clear. As appealing as this option sounds, one has to wonder how many artists would benefit from this kind of price re-setting. Even for those who need to headline numbers, that's a momentary thing in what they hope will be much longer term markets.

Also, more will try than can succeed. How’s that going to play out?

Nonetheless, Sotheby’s is publicly inviting artists and their galleries to use their platform in ways that are likely to morph unexpectedly. That could end up being a good thing for the art market.

At least it accomplishes one thing. The Artist’s Choice program acknowledges that the artificial conflict between galleries and auction houses has been over for a very long time.

.png?width=880&name=Huang%20Yuxing%20(1).png)