Five Sales That Changed the Art Market in 2021

From Beeple to Banksy to George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware—these five sales just might be turning points toward the future

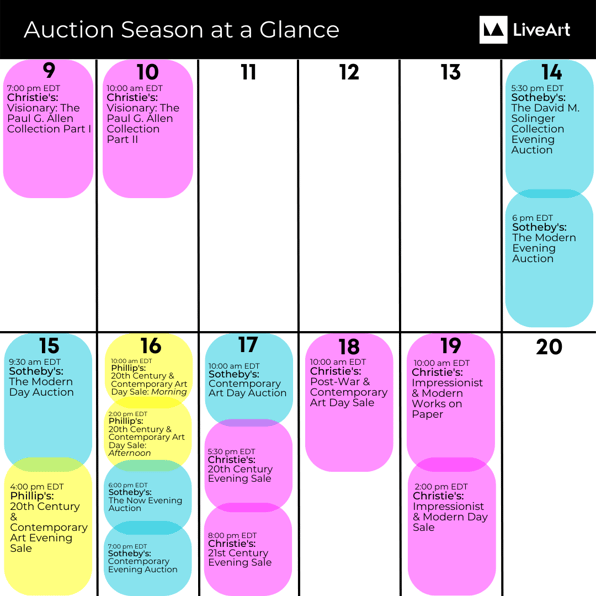

No sensible person looking at the fear and improvisation that overtook the art market in 2020 would have predicted the spectacular year of 2021. A year ago, everything about the art market seemed poised for change. The traditional auction calendar looked like it would be replaced with a schedule of hybrid sales broadcast regularly from everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Art, it was assumed, would have to hibernate until in-person exhibitions could be held again

Today, the art world looks very much the same as before the pandemic—and yet so very, very different. With that in mind, we took a look back at five sales from 2021 that might tell us a bit more about what’s coming in 2022 and beyond.

Beeple is the Big Bang of Digital Art

On December 11, 2020, Mike Winkelmann—already a hugely popular artist through Instagram—launched his Beeple:Everydays collection on Nifty Gateway. The success of that sale snowballed four months later into the $69 million sale of the entire Everydays: The First 5000 Days series at Christie’s in March of 2021. In his video promoting the December sale, Winkelmann compared NFTs to street art, admiring the achievements of Banksy, and collectibles, citing the success of KAWS. He was right—though NFTs would turn out to be bigger than both. The Everydays sale was not very different from some of the record-setting sales for other living artists like Jeff Koons’s Orange Balloon Dog (the buyers had their own investment in Beeple’s work), it did create the Big Bang of NFTs in the art world. One thing worth noting, Beeple’s next big sale at Christie’s held just in November was for a piece of digital art mounted in a physical armature. As his work becomes more valuable, it is moving away from being purely digital and toward more conventional art.

Banksy Shreds the Market

The more prank artist Banksy derides the art market, the more valuable his work becomes. Like an insult comic who endears himself to his victims, any hope Banksy had of shaming art collectors has simply vanished. Not satisfied with mocking collectors with his Morons, 2007—its inscription taunts collectors with, “I can’t believe you morons actually buy this shit”—Bansky significantly raised the stakes when he convinced Sotheby’s to take a consignment of his work, Girl with Balloon, for the October, 2018 Contemporary art Evening sale. Hidden inside the frame of the work was a shredder. Banksy’s plan was to activate the shredder right after the lot closed. It was only an accident that Sotheby’s placed the work as the final lot of the evening. Yet the dramatic crescendo of the $1.36 million sale followed quickly by the work beginning to self-destruct could not have been better planned. Unfortunately, the shredder malfunctioned. The work that was meant to be destroyed remained in a liminal state: half preserved; half shredded. The savvy buyer decided to keep the work. Bansky played along and renamed it Love Is the Bin. Three years later the work set a new record for Banksy at $25 million. The lesson lies not in Banksy’s desire to Épater la bourgeoisie but in the auction as theater of value. The pandemic has created a much larger audience for art auctions. Fine art is one of the few types of assets where the sale is its own marketing for the value of the work. We see that clearly in this Banksy piece which would have been worthless had the prank worked. But it would also have been worthless—or nowhere near as valuable—had it never been sold at an auction at all. The sale and subsequent partial destruction is indeed the art work, not the image itself.

Frida Kahlo’s Private Parrot Party

In the depths of the August art market doldrums, gadfly Kenny Schachter spilled the beans on an interesting innovation at Christie’s. Although the auction house won’t confirm it, Schachter’s report that Christie’s held a private auction for Frida Kahlo’s Me and My Parrots from 1941 is significant not only for the supposed $130 million price tag but also for the innovation of a private auction. Auctions are particularly useful for works that are difficult to price. Private sales often falter when the buyer is not fully convinced that others would pay as much as they are willing to pay. And, vice versa, buyers often spend more when they see proof of other interest. Here, Christie’s split the baby. They invited a select group of potential buyers and held a private auction. Can that work for many artists? No. Did the sale have a significant effect on the market for Frida Kahlo? Arguably, yes. A few months later, Sotheby’s set an auction record for Kahlo with Diego y yo from 1949. That work set a dramatic new record price for the artist at nearly $35 million or more than four times her previous record public price. What’s $35 million compared to $130 million? Quite a lot, actually. Forget the relative size and visual appeal of the two works, in the small world that is the art market, it was surely easier to get a guarantor to pay $35 million for Diego y yo after the $130 million sale than before and easier to get a collector to pay $130 million privately for a Frida Kahlo (when no Kahlo had sold for more than $8 million before) when the buyer could see other bids at similar level.

Taking a Gamble on Picasso

Sotheby’s had their own selling innovation this Autumn. The Picasso market is never really quiet but it had been relatively tame for several years. There had been no new top ten price for the artist until this Spring when Christie’s sold a 1932 painting of Marie-Thérèse Walter for $103 million. Whether it was the new vigor or simply the novelty of having works associated with Las Vegas, Sotheby’s decided to take a calculated risk with works that had been integral to MGM’s Picasso restaurant in Las Vegas. In the age of globally webcast hybrid auctions, Sotheby’s figured it could attract enough buyers to make a successful remote event. Sotheby’s and MGM’s clients jumped at the excuse to take a break from their pandemic isolation and go to Vegas for a weekend of action, at the tables and on the auction block. The event succeeded better than expectations with the auction totaling $108.8 million. Perhaps more important to their long-term business, Sotheby’s was able to put their sales team and their buyers in an environment where they could spend quality time together. The results spoke for themselves.

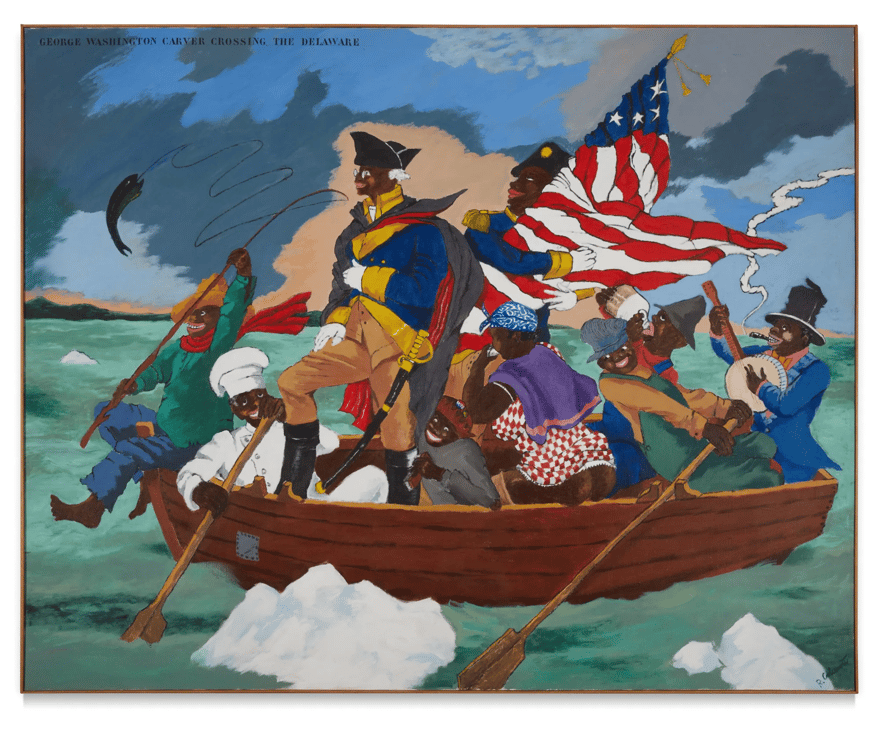

Robert Colescott Crosses Over

What Banksy and Frido Kahlo have in common is that the high-water mark for the auction prices was pushed way, way up in 2021. Banksy’s top price more than doubled in 2021—and then rose from there another 15%. Neither of those price leaps matches the sale of Robert Colescott’s George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware from 1975, which made a price ten times his previous auction record when it sold in May. The real news was that the buyer was the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art which will open in Los Angeles in 2023. More than just another well-funded LA museum, the Lucas and its Colescott acquisition represent the leading edge of institution building taking place around the world. Public and private museums are opening at fast clip. Each one of these museums has a primary mission to acquire art. The art these museums are looking for is increasingly work that is truly representative and equitable. As a driving force in the future of the art market, no other influence could be as profound in determining what kind of art by which artists becomes valuable in the future. ““A correction would require you to collect only Black art for the next 400 years to make this right—exclusively,” Gagosian’s Antwaun Sargent pointed out in Harper’s Bazaar. “The absurdity of that shows you the absurdity of this present predicament.”