Is Jordy Kerwick, the Darling of the Art Bros, For Real?

With a gallery show opening in Hong Kong, the Australian’s Instagram-fueled market is taking off

The art market is changing. Or maybe it’s not. Who knows? But there is something currently happening in the art market that’s worth paying attention to. It seems to be best illustrated by the career of naive painter Jordy Kerwick, who has a show opening this weekend at Kevin Poon’s Woaw Gallery in Hong Kong.

On the face of it, Kerwick is an unlikely success story. An Australian who lives in the heart of the heart of the French countryside with his academically-trained painter partner, he has no gallery guiding his rise, but his work is highly sought-after by collectors.

It’s not just where the demand is coming from but who is buying and promoting his work. Sofia Richie, the daughter of Lionel Richie, showed off Kerwick’s work to her 7 million Instagram followers in November by taking a four-shot carousel of the Olsen twins' New York store for their fashion brand, The Row. It culminates in a large Kerwick work on display. Richie is no idle wannabe here. Richie has a Kerwick of her own. She and the Olsens are both advised by Vito Schnabel who has been pushing Kerwick.

It’s not just the social-media famous and the famous famous who are buying either. Richard Prince—a canny collector himself who previously bought work by Genieve Figgis and helped turn her into a market darling—has also bought Kerwick’s work.

Miami’s John Marquez, the real estate developer and restaurateur, bought Kerwick early. Then he branched out, commissioning Kerwick’s wife Ces McCully to design a basketball court for his home and even acquiring one of Kerwick’s NFTs. Kerwick’s work is now in demand across the archipelago of art collectors on the West and East coasts of the US, in Europe and increasingly across Asia.

The market change that Kerwick represents isn’t the global growth, though that’s part of it. The change is Kerwick’s rise through Instagram and his centerless market. No one doubts that Instagram has had a huge impact on discovery in the art market. But one of the questions surrounding the upward whoosh of Kerwick’s market is whether his art is a beneficiary of Instagram’s somewhat random luck or a canny exploiter of it.

Although Jordy Kerwick says he’s drawn all his life, he only began actually painting in the beginning of 2016. Before that, Kerwick was a bit of guy’s guy, making a living in music and married to the painter Rachel, who goes by Ces, McCully. Naive painters usually have a distinctive, autograph kind of style. But Kerwick’s work seems to have migrated in a relatively short amount of time from a flat still-life style reminiscent of Jonas Wood and now Hillary Pecis to a naive, graffiti-like style that seems beholden to Robert Nava to finally settling into distinctive fantasy animals often with two heads.

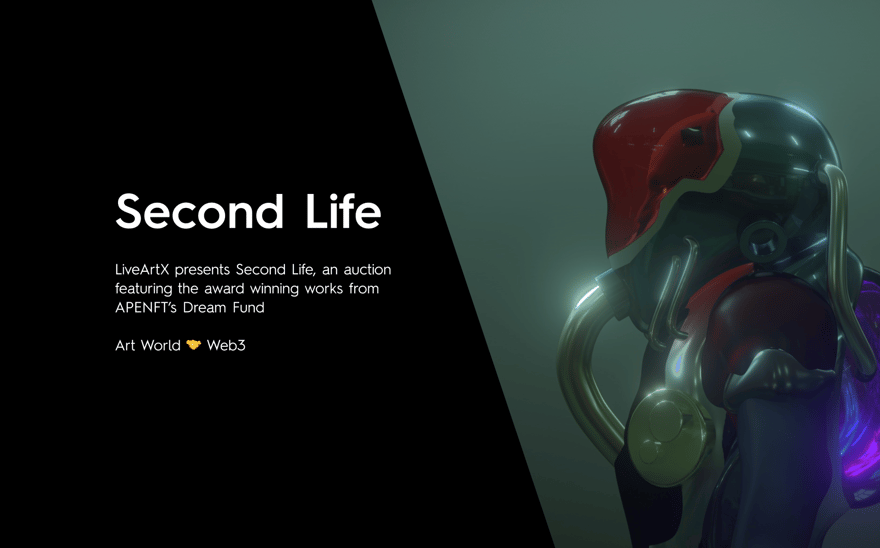

“Kerwick makes a kind of young, punky art with a hardcore aesthetic,” says LiveArt’s Executive Vice President, “that plays into a path that other artist’s markets have followed. There’s a couple of other artists in this narrative like Robert Nava and Katherine Bernhardt that quickly speak to a whole group of collectors.”

Five years isn’t a long time in an artist’s output. But Kerwick hasn’t been holding back. Nor has his short career or substantial output held him back. Instagram put him in touch with a range of gallerists around the world that led to having his work included in group shows.

Instagram also seems to have been a venue for his own sales. He takes care to feature frequent views of his studio which gives everyone and anyone a sense of the works in progress there. Some collectors report that Kerwick was easy to approach and accommodating when they wanted to acquire multiple examples of his work directly from the studio. Depending on your point of view, Kerwick is either being democratic by making his work so widely available to see and to buy, or he’s dangling the work in front of speculators.

That brings us back to the question posed by Kerwick’s market. The art may be naive, but no one collecting it seems to be. Kerwick’s buyers seem to be very savvy market participants, maybe too savvy. Some, like Marquez, may to have come to him after acquiring work by Nava. Others seem drawn to the safety of numbers.

Kerwick’s market has been built somewhat on the experience of other market-oriented artists who produced a substantial volume of work and allowed speculators to freely participate. In Kerwick’s case, his work is available from so many different sources—dozens of galleries seem to be offering the work or holding shows—because he’s had no single gallery managing his market. Like any ambitious artist, he’s been eager to spread work around and meet demand. This is not how galleries tend to operate where a great deal of effort goes into placing work with influential collectors and, perhaps, strong-arming a few to get work into museums.

The happy-go-lucky Kerwick hardly seems concerned with that. Though lately he seems to have either raised his ambitions to the level of having his work collected by museums or recognized the value of having his work in institutions to get to the next price point in the global market.

In that sense, maybe nothing has changed in the art market; Kerwick’s Instagram launch was just his only way to get his art seen. Where some more jaded collectors see his work as a pastiche of better artists, in interviews Kerwick references a number of Australian artists whose work he admires and emulates. Many in the art world see Jonas Wood but Kerwick is thinking Fabrizio Biviano. The artist he believes to be the epitome of Australian talent, Rhys Lee, hardly fits in with the stable of artists prized by the global fraternity of art bros. Kerwick is naive, yet his work comes off as far more authentic than the artists he cites as influences. Which brings us back to the place where we started: is Jordy Kerwick for real?