Can Wayne Thiebaud Win Big?

The Fondation Beyeler show is just the first step in his growing global reputation. With recent record prices, can a big market follow?

The market for Wayne Thiebaud’s art has taken a significant upwards turn in the last five years. Although the artist died at the age of 101 on Christmas Day in 2021, the rise in Thiebaud prices seems unconnected to his death. With the opening of an important retrospective at the influential Fondation Beyeler, it is worth taking a look back at the market for this quintessentially American painter.

For far too long, the mormon-raised Thiebaud has been treated as a novelty or a regional artist, anything but the major painter that he is. After an apprenticeship with Walt Disney, Thiebaud became a cartoonist and designer before becoming a teacher. For 30 years, the artist was a professor at the University of California in Davis.

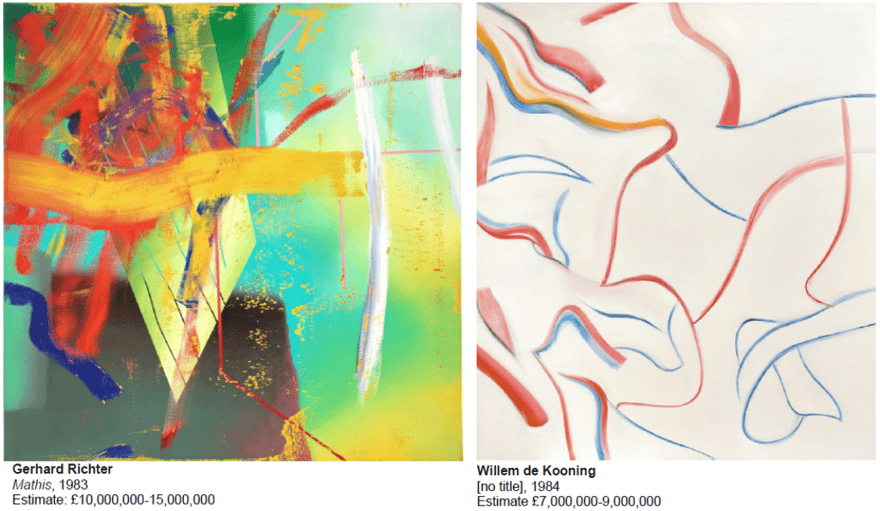

During the mid-1950s, Thiebaud took leave and moved to New York. Spurred on by a conversation with Willem de Kooning, who told him he had to find something he really knew about and was really interested in to pursue both as style and subject matter, he decided to take himself seriously as a painter.

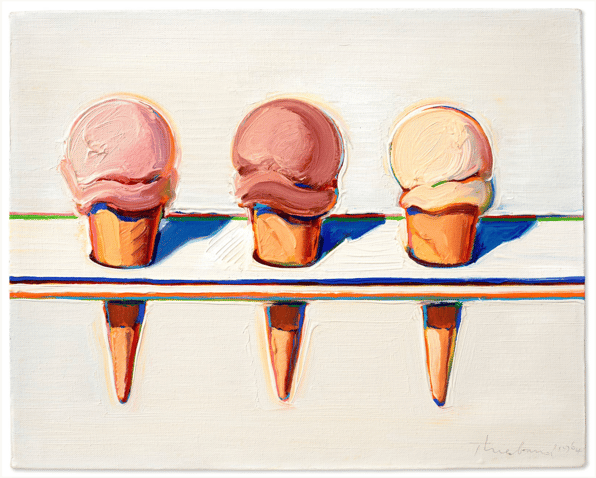

The Pie Guy

Following de Kooning’s advice, “I took the canvas and made some ovals, thinking about Cézanne—the cube, the cone and the sphere—and put some triangles over them and thought, well, that maybe could represent a pie on a plate,” he told Jason Edward Kaufman in an interview that appears in the catalogue for the Beyeler show. “I said, alright, I’ll go ahead with this and I’ll make them into pies. I was really enjoying myself… and as I finished, I looked at it, and said, my god I just painted a bunch of pies. That’s going to be the end of me as a serious painter.”

It wasn’t the end of him as a painter but it did stand in the way of many artists taking him seriously. When Thiebaud joined Allan Stone’s gallery for his first show in 1962, the dealer was heavily involved in representing Abstract Expressionists. Supposedly Barnett Newman had organized Stone’s other artists to deliver an ultimatum, “get rid of the pie guy.” But the dealer had already become entranced by Thiebaud’s work.

After their first meeting, Thiebaud left several un-stretched paintings with Stone which the dealer decided to display in his apartment among his AbEx works by de Kooning and others. “I noticed these things really held their own,” he says in a documentary made by his daughter. “You put a Thiebaud next to a de Kooning, Thiebaud wasn’t going anywhere.”

From 1962 until his death in 2006, Allan Stone was Thiebaud’s dealer and stood at the center of his market. Although Thiebaud would not receive a major New York retrospective until 2000 when he was 80 years old, Stone was able to sell important works to clients and influential collectors like Larry Aldrich, Joseph Hirshhorn, Carter Burden, Leon Krashaur and Robert and Beatrice Mayer.

There were some significant auction sales in the 80s. A depiction of heart cakes sold for $605,000; and a painting of cliffs made $495,000. In 1988, total sales at auction broke $1 million. The next year they shot up to $1.69 million before retreating for nearly a decade.

By the end of the 1980s, Stone had sold a work to the National Gallery for a million dollars, an important milestone. Then, in 1997, a divorce brought a major work from Thiebaud’s first show in 1962, Bakery Counter, to auction. Famed collector Hunk Anderson had tried to buy Bakery Counter privately but was put off by the $100,000 asking price. He would later pay more than that for a work depicting pinball machines. Bakery Counter was offered with a half-million dollar estimate. At the end of the bidding, it had sold for $1.7 million. The buyer, Barney Ebsworth, went out of his way to tell the consignor after the sale that he would have paid more for the painting.

In 1997, Thiebaud’s auction total was $2.2 million based mostly on the Bakery Counter sale. In 2001, the Whitney’s retrospective, put together by SFMoMA, helped collectors take Thiebaud a little more seriously. Buyers spent $1.4 million at auction in 2000 and $5 million in 2002. But the market would have to wait until 2006 for total auction sales to top that again at $6 million.

Installation view of Wayne Thiebaud: A Paintings Retrospective (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, June 28–September 23, 2001). Photography by Jerry L. Thompson

Installation view of Wayne Thiebaud: A Paintings Retrospective (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, June 28–September 23, 2001). Photography by Jerry L. Thompson

Allan Stone Dies

Allan Stone died in 2006. In 2007, Stone’s heirs held an auction that included five works by Thiebaud. That helped contribute to the $19 million Thiebaud total that year.

Auction markets are driven by demand but also supply. When good Thiebauds come to market, buyers respond. The heirs held another sale in 2011 that included 18 Thiebauds. All but one sold for $27.5 million. In the second Stone sale, Pies from 1961 set a new record price at $4 million and Four Pinball Machines (study) from 1962 made $3.6 million. There were other multi-million dollar Thiebauds in that sale. All together in 2011, 35 works were sold with a total of $40 million for the year. It would take until 2022 to surpass that figure again.

Selling so much work in one year would tax any artist’s market. On the private side, Thiebaud switched dealers after the death of his son Paul in 2010 who had taken over from Allan Stone in 2006. In 2011, the Acquavella family took over representation. The gallery’s stature helped signal to the collecting community that Thiebaud was taken seriously by serious collectors. Still, the Acquavellas had to show that Thiebaud was more than just the “pie guy.”

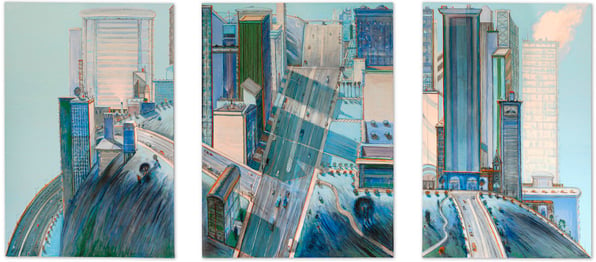

And they did—by holding shows focused on Thiebaud’s portraits, landscapes, cityscapes and other still lives. Acquavella also took a page from Allan Stone’s book and showed Thiebaud alongside Richard Diebenkorn, another artist with a plangent reputation but a muted market. Diebenkorn had once been underestimated as a “California” artist too. (Christie’s would supercharge the Diebenkorn market in 2018 when it sold a collection of 22 works for $43 million.)

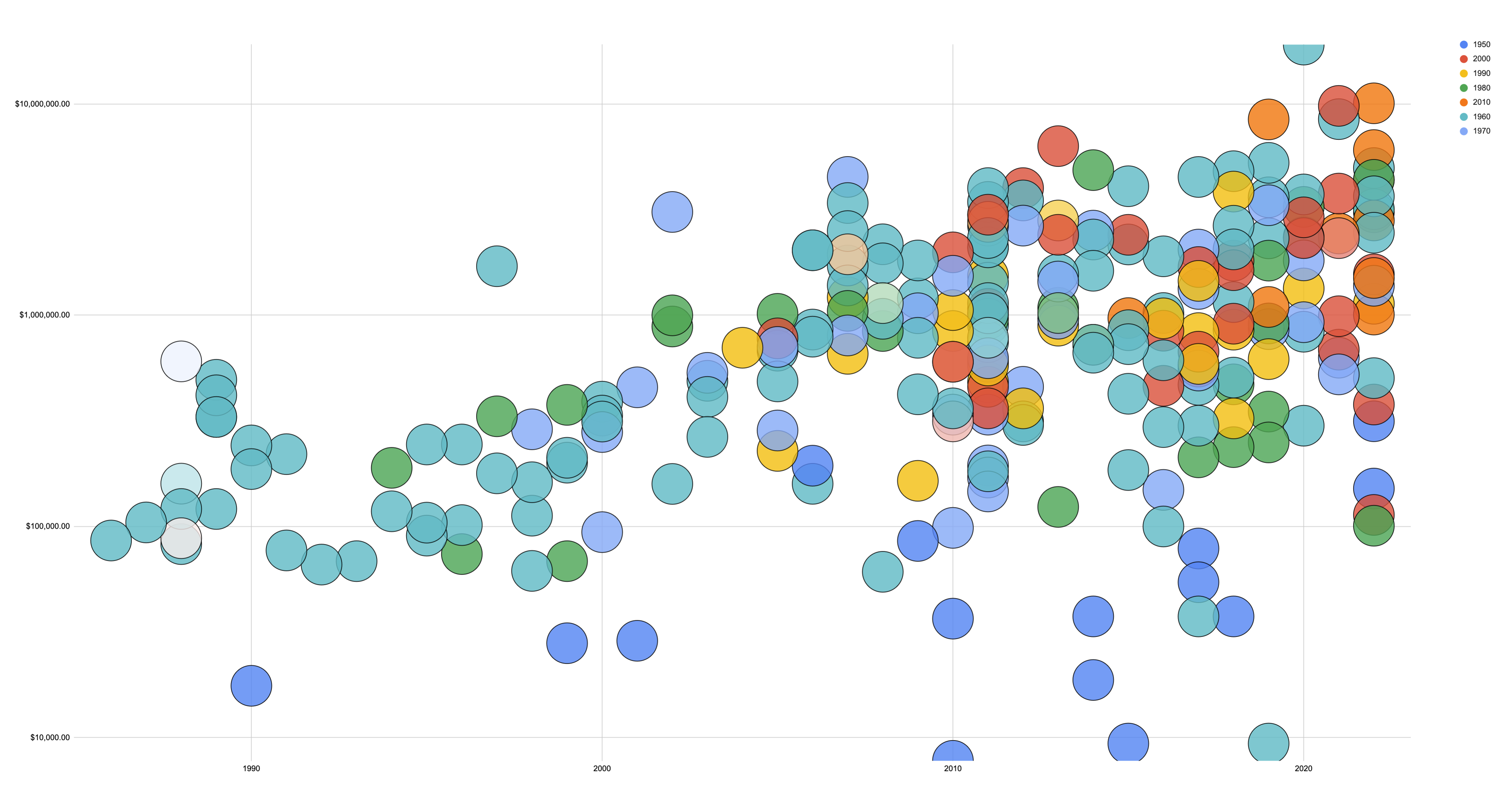

Few may have understood that Cézanne lay at the bottom of Thiebaud’s practice but the market had a paradoxical approach to his work: he was limited by the success of the pies but that was the work the market valued, especially the early work. Until 2010, the auction market was dominated by works from the early 60s with occasional works from the 70s and 80s.

The Acquavella Effect

Since Acquavella took over, the auction market has seen a wider appetite for works from all periods, including the 21st Century. Over time, pricing has shifted from year of creation to imagery and size. Thiebaud is fairly unique among artists in that his work repeats subject matter over many decades without an obvious change of style. In 2013, the 4-foot-by-5-foot Two Jackpots painted in 2005 sold at auction for a new record price of $6.3 million. The buyer was happy to ignore the date because the work looked and felt like Thiebaud of the highest quality. It helped that the picture was large too.

Wayne Thiebaud auction sales shown on a log scale for visibility. Works are color coded by decade of creation. After 2010, a greater number of works from later decades have sold at auction and for prices at the same level as works from the 1960s.

Wayne Thiebaud auction sales shown on a log scale for visibility. Works are color coded by decade of creation. After 2010, a greater number of works from later decades have sold at auction and for prices at the same level as works from the 1960s.

It would take another six years before that price was beaten again. Again, it was by a 21st Century picture. Sotheby’s sold the 4x6-foot Encased Cakes from 2011 for $8.4 million in 2019. The buyer didn’t hold it long. They sold two-and-a-half years later at Poly Auction in Hong Kong for $10 million.

The sale is significant for a couple of reasons. First, Poly’s primary constituency is Mainland Chinese collectors. The sale shows that Asian collectors have Thiebaud on their wishlist and they’re willing to pay a premium (even for a work so recently sold.) Second, the $10 million price coupled with $8.4 million paid for one of the artist’s Wimbledon pictures, Toweling Off from 1968 the year before were strong confirmation prices against the stunning record price of $19 million set in 2020 for Four Pinball Machines from 1962.

The Pinball Effect

Nearly six-feet square and from the seminal year of 1962, Four Pinball Machines ticks every box of art market value. The seller was California investment manager Ken Siebel who purchased the work from developer and landowner Donald Bren. Bren had bought the painting in the wake of the Whitney’s Thiebaud retrospective which featured Four Pinball Machines as the opening work of the exhibition. He sold to the Siebels not long after.

Like the artist himself, the painting is more than a nostalgic evocation of American popular culture. The pinball machines depicted reference Thiebaud’s contemporaries, Jasper Johns and Frank Stella; the work foreshadows the collapse of high and low culture while still projecting the kind of wallpower collectors and institutions crave.

More important for the overall growth of the Thiebaud market, since 2017 twice as many works have sold in the $3-5 million price band than in the previous six year period. Seven times as many works have sold above $5 million in the last three years than ever before.

With substantial museum representation now, growing interest from museums abroad like the Beyeler, and rising value for his works, Thiebaud has the potential to provide market leadership in the future. His market will need more infrastructure but Acquavella now represents the artist’s foundation. Last year, $53 million in Thiebaud’s work sold at auction. That places Thiebaud 41st in market share, well below Gerhard Richter who sold four times as much and sits at number 8. With the right market infrastructure and continuing visibility in museums around the world, there’s plenty of room to grow.

%20copy.jpeg?width=880&name=2020_NYR_19657_0063_000(wayne_thiebaud_four_pinball_machines)%20copy.jpeg)