Scrolly Gnoli

How the enigmatic Italian painter prefigured—and defined—Instagram before it ever happened

Tightly framed, zoomed in, and even claustrophobic renderings of objects are having a moment right now. From art fairs to Instagram–or, more to the point, art fairs on Instagram–a particular aesthetic has been cropping up. You can see it in the work of Julie Curtiss whose show just opened at Anton Kern in New York, as well as in the work of Sally Kindberg and Sarah Miska.

It would be easy to explain the trend by blaming social media. Artworks that look good on Instagram attract attention; attention leads to representation; representation leads to sales. And that might be the reason we’re seeing this pictorial strategy all of a sudden.

However, we can also remove Instagram, social media, and even the internet from the equation altogether and still find an eerie precursor of these artists in the ill-fated Italian painter Domenico Gnoli.

Fifty years before croppers appeared in the art world, Gnoli was making his own enigmatic macro-lens works. Gnoli is best known for taking a fraction of an object–a single curl, a shirt collar, a high-heeled shoe–and depicting it as monumentally important. His use of scale and framing turned peripheral details into central subjects, creating cultural portraits of importance out of details you might have missed.

Born in Rome in 1933, Gnoli died of cancer at age 36 in 1970, shortly after his first New York exhibition at Sidney Janis Gallery. His short life and idiosyncratic style left him on the outskirts of art history–and the art market–until 2012 when Luxembourg & Dayan held a show of Gnoli's paintings.

Though individual works evoke both Pop art and Surrealism, Gnoli is not properly categorized within either movement. “Gnoli might share with his Pop contemporaries the passion for immortalizing everyday objects in all their blatant banality,” wrote Cecilia Alemani in an essay accompanying Luxembourg & Dayan’s second solo presentation of Gnoli’s work in 2018, “but his practice diverges from Pop because he is not interested in using painting as cultural or social commentary.”

At the same time, “Gnoli’s work has also often been described as a descendant of the tradition of metaphysical painting and Surrealism,” but “[h]is paintings do not construct stories or conjure dramas.”

How to define him, then? Alemani suggests that “he embraces a realism devoid of narrative.”

How also to explain the gaps between Gnoli’s distinctive style and the sudden appearance of so many artists for whom he appears to be a powerful progenitor. Gnoli was ahead of his time. Alemani suggests Gnoli’s practice has more in common with the “commodity art” of the 1980s. “The history of twentieth-century art is the history of our relationship to objects,” Alemani wrote. “Gnoli conceived a world of pure products gone crazy—a universe in which commodities grow to fill the entire field of vision, becoming metaphors for the mechanisms of seduction.” That same relationship has only grown more visible, and more fraught, in the age of social media.

Instagram’s tyranny of the commodity might explain why there is a Gnoli show currently at the Fondazione Prada. Even so, Gnoli’s successors are making a case for using this visual strategy to subvert it.

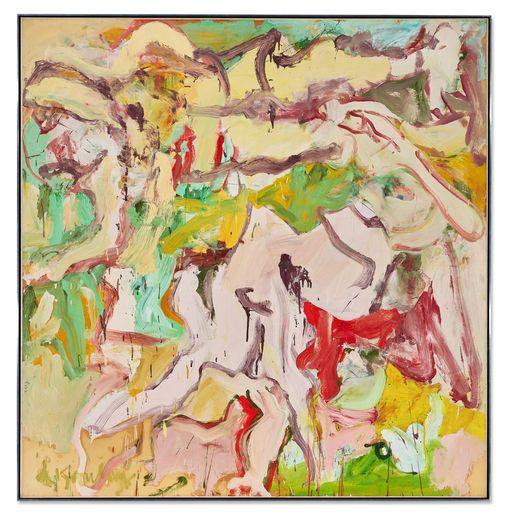

Maquette, 1967, Domenico Gnoli. Private collection. Image: © Domenico Gnoli, SIAE/DACS, London 2022

Maquette, 1967, Domenico Gnoli. Private collection. Image: © Domenico Gnoli, SIAE/DACS, London 2022

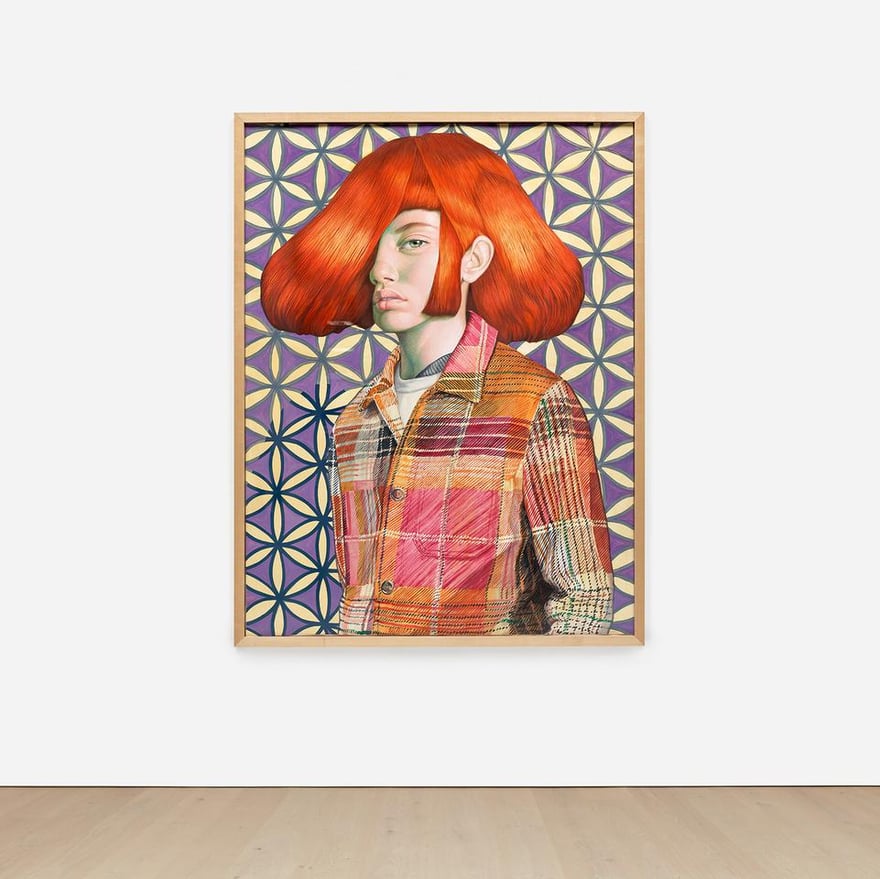

At Anton Kern Gallery in New York, Julie Curtiss: Somnambules is on view through October 22. Curtiss’s pandemic-induced insomnia seems to have produced paintings that evoke an almost “sleepscrolling.” Her faceless figures set in larger compositions reduce figures to the details that define them–clothing, hats, hair, and more.

%2c%202022%2c%20Julie%20Curtiss.png?width=2273&name=Dancers%20in%20the%20dark%20(Moon)%2c%202022%2c%20Julie%20Curtiss.png) Dancers in the dark (Moon), 2022, Julie Curtiss. Anton Kern Gallery

Dancers in the dark (Moon), 2022, Julie Curtiss. Anton Kern Gallery

Sally Kindberg’s Lay of the Land, on view at Thierry Goldberg Gallery, is filled with polyester pants and double bubble gum. It also taps into a spooky timelessness. “They have a cut-out-of-time quality,” Alasdair Duncan writes about the show. While the compositions are seemingly perfectly framed and tinted for an Instagram feed, the objects within them could be situated anytime within the past eighty years or so. The effect is uncanny.

Next month, Lyles & King will present A Cautionary Tail, a solo exhibition of works by Sarah Miska. The show follows her summer solo show Tidy at Friends Indeed Gallery. Miska’s paintings depict the equestrian world through the tiny tidy details by which it is defined. “Despite the diminutive size of these details, they fill the canvas with a sinister excess,” writes Olivian Cha for the exhibition text.

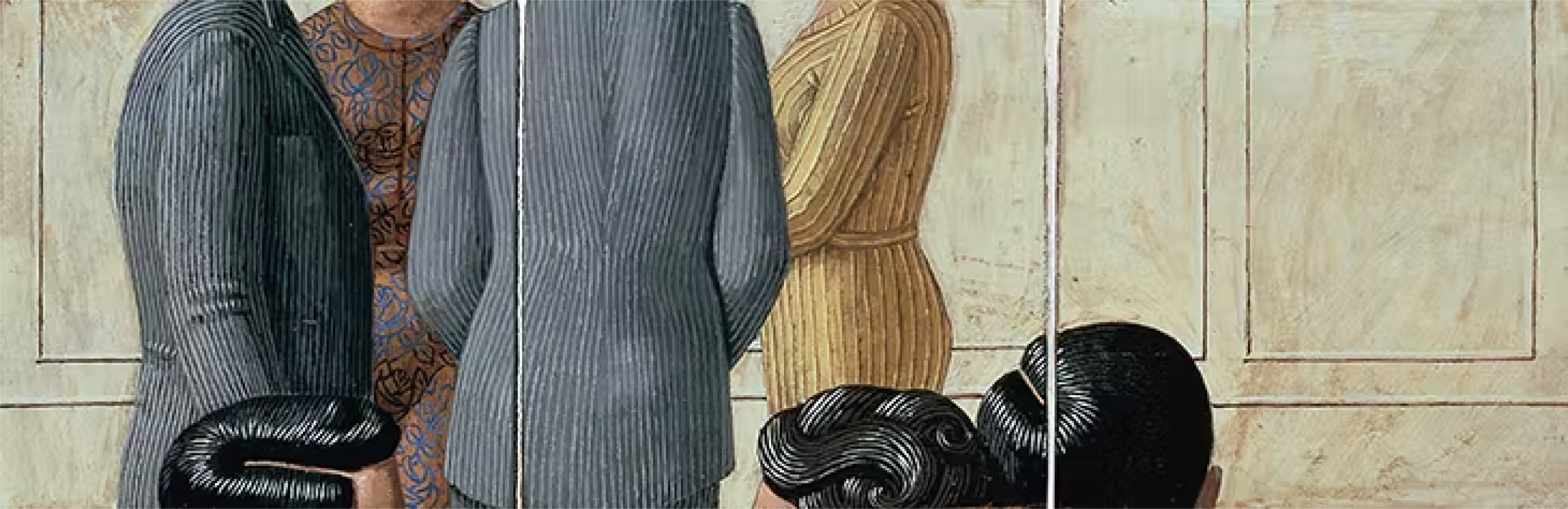

Sally Kindberg, Ocean Liner, 2022. Thierry Goldberg Gallery // Sarah Miska, Pearl Hair Net, 2022. Friends Indeed Gallery

Sally Kindberg, Ocean Liner, 2022. Thierry Goldberg Gallery // Sarah Miska, Pearl Hair Net, 2022. Friends Indeed Gallery

The tightly cropped figurative works of these emerging artists present objects in a manner that is precise but not photorealistic. With a hyperfocus on the beautiful, we must assume the ugly and sinister elements of life lay just out of frame–much like on Instagram.